by Neville Jones | Nov 26, 2021 | Thinking

Employer branding and The Great Resignation

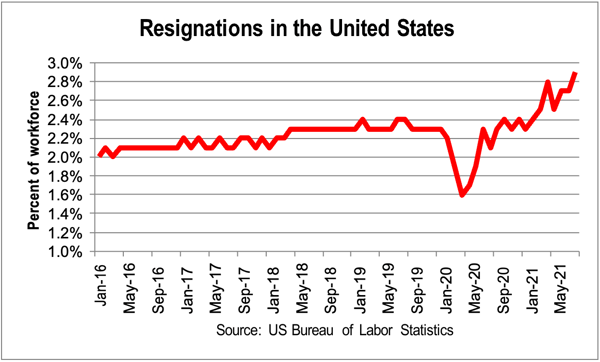

On May 30, 2021, NBC published an article by Anthony Klotz, associate professor of management at Texas A&M University. The article, provocatively titled “The Covid vaccine means a return to work. And a wave of resignations.” introduced the term The Great Resignation and sought to explain the alarming increase in the resignation rate in the US workforce after a transient drop. (Klotz) From 2016 to late 2019 the “quit rate” stayed in the range 2.1% to 2.3% of the workforce. In twenty years, the quit rate had never exceeded 2.4%. (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

As the pandemic gripped the economy in the northern winter the quit rate dropped sharply to 1.6%. It then bounced immediately and just as quickly as it fell, rose straight past the “normal” zone to 2.9% in August 2021.

Klotz offered three reasons for this rapid, material increase:

- There was a catch up. Contemplated resignations were put on hold during lockdowns and other confidence-sapping initiatives. But when a degree of certainty returned, the deferred resignations plans became a priority again and the backlog of resignations cleared.

- The Pandemic Epiphany. With a profound change being forced upon their lives, workers re-evaluated what was important to them. Employing the “boiled frog” metaphor, workers were suddenly lifted from the pot and given the opportunity to question the value of diving back in.

- Workers resent being forced back into the office. Klotz called this “the big one”. Millions of workers have experienced working from home for the first time and many enjoyed it. This mode of work addresses the fundamental human needs of autonomy, flexibility and freedom. “As companies make plans to end remote work, millions of workers are experiencing the most severe case of the Sunday Scaries1 of their lives.”

The common thread in these three drivers is a re-evaluation of the balance between two of the most important life-goals: happiness and meaning. “When viewed through this perspective, what is driving The Great Resignation is fairly straightforward: The pandemic has made many realise their job does not contribute enough (or at all) to their pursuit for happiness and meaning and they have decided to invest their energy elsewhere – in new jobs, new careers or in other aspects of their lives (eg, family, travel, creative endeavours).”

A month after the Klotz article appeared, Forbes magazine published an article by senior contributor, Jack Kelly, invoking research by insurance giant Prudential. That research found that “48% of Americans are rethinking the type of job they want post-pandemic.” (Kelly, Millions of workers plan to switch jobs in pursuit of life balance)

Even more shocking was research by Monster.com that found that 95% of workers said they were thinking of quitting their jobs and that burnout was the most commonly cited reason for wanting to leave. That was a survey of 649 workers in the US. (Cooban)

After a significantly larger study in March 2021, Microsoft published their annual Work Trends Index which found that 40% of the 30,000 respondents in 31 countries were “considering leaving their employer this year.” The title of the report is “The Next Great Disruption Is Hybrid Work – Are We Ready?” (Microsoft)

It’s unlikely that any business is ready for the mass resignations that these surveys seem to predict but perhaps it won’t turn out that way.

Thinking is not the same as doing

Jack Kelly, in a different and notably earlier article in Forbes offered some reasons for “Why the Great Resignation is greatly exaggerated.” (Kelly, Why the Great Resignation is greatly exaggerated) He observes that some sectors, especially low-skill, low-wage sectors have low barriers to labor mobility. Many of these sectors have fared well in the pandemic and are offering slightly higher wages and even bonuses. That’s enough to motivate a job change for many. He also observes that it’s different in white-collar sectors. Many companies are still stuck in the 2020 mindset. Workers will not jump unless they can land in a better place.

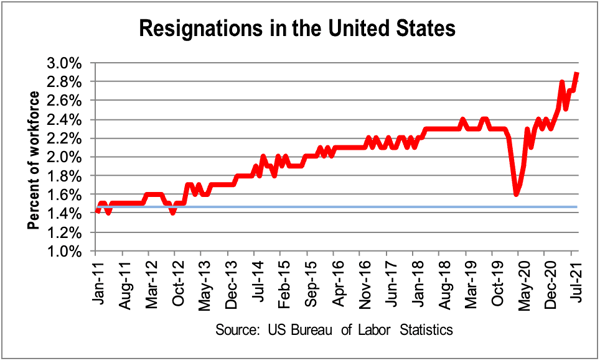

While we’re pausing to reflect on what might really be going on, let’s look again at the “Quit” series that motivated Professor Klotz to write his piece on The Great Resignation. If we widen the view to look at all the data that are available in that series, we see something different. The current “quit” rate is less than half a percentage point above the long-term trend, quite possibly the overshoot in catchup that Klotz himself refers to.

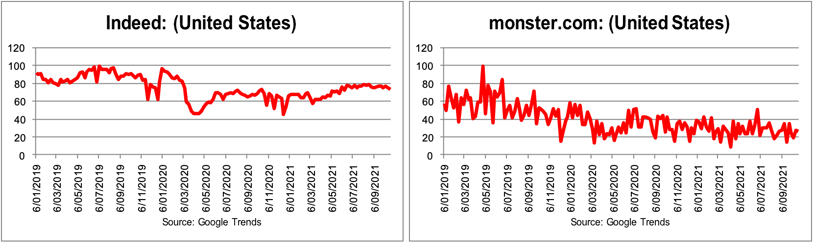

In his “exaggerated” article, Kelly reminds us that “in surveys, respondents can be brave and talk tough”. Indeed, Seth Stephens-Davidowitz submits in “Everybody lies” that intentions surveys are next to useless. (Stephens-Davidowitz and Pinker) He would be likely to dismiss surveys that found that 95% or even 40% of workers were considering a job or career change. Instead, he would be more persuaded by actions, specifically things that people do when they think nobody is watching. Like Google searches. An analysis of Google searches for major job sites, Indeed.com and Monster.com from pre-pandemic to date reveals a slight downwards trend.

Does it matter that employees are day-dreaming about job changes?

So, what are the implications of 40%-95% of the workforce saying they’re considering quitting their jobs, but not actually doing it? It would seem a folly for employers to ignore this phenomenon. It’s more likely that employers think that the drivers don’t apply to their workforce.

A PWC survey of 1800 Australian employees and their employers conducted in September 2021 revealed some disturbing gaps in what employees expect of their employers, compared with what the employers think their employees want. (PWC)

The largest gap in understanding was that employers believe that the most important factor to employees is “values alignment between worker and organisation”. Wrong. Employees ranked that 16th! Employees ranked “working with good co-workers” as most important but employers thought that would rank 13th. “Working from home” was 9th most important to employees but employers thought it would rank 17th. “Pay” was ranked 3rd by employees and employers thought it would be 8th.

In short, employers simply don’t know what their employees want. This is quite disturbing, given the number of employee satisfaction surveys that have rolled out across industry. A leader who has committed to expensive and time-consuming employee surveys could reasonably believe that they have a good handle on what their employees want. But the evidence is clearly to the contrary. How could this happen?

The PWC survey was of a single point in time. As such, it affords the survey designers a specific luxury: they were free to design the questions from scratch. Conversely, most ES surveys are longitudinal studies designed to identify trends in sentiment. The results reveal progress that managers are making along each of the dimensions measured. Test-Remedy- Repeat. All very sensible but it means that you have to ask essentially the same questions every year. Consequently, not many longitudinal ES surveys will ask “would you prefer weekly staff meetings to be in-person or on Zoom”. Zoom wasn’t a thing when the survey was designed.

The probability of a “that doesn’t apply to me” reaction to this report by employers is very high. 48% of the surveyed employers have no plans to update their Employee Value Proposition.

So, what do employees really want?

The question of what employees really want is a trick that is easily fallen for. The answer is somewhat reminiscent of Billy Connolly’s wonderful skit on “demands” in which he finishes with “We want f**king more tomorrow, and the demands will all be changed then so f**king stay awake!” (Connolly)

The environment is changing. The pandemic epiphany is real. Employees really are reconsidering how to satisfy their happiness and meaning life-goals. The answer to the question depends on when you ask it.

Prior to the pandemic, flexible working arrangements, especially work-from-home was only a dream for most workers. For a start, fewer than 40% of all work-roles can actually be performed at home. (Dingel and Neiman) For most of those, their bosses distrusted the motivation for work-from-home, believing they would see a loss in productivity. “Historically, there has been a perception in many organisations that if employees were not seen, they weren’t working—or at least not as effectively as they would in the office,” says Lauren Mason, a principal and senior consultant at Mercer. (See Proximity Bias below.)

Then the pandemic forced their hand. In Australia the mandate was expressed as “if you can work from home, then you must work from home.” Non-essential businesses were shuttered. For the first time, white-collar employers were forced to make work-from-home work.

Employers need not have worried about productivity. A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research reported that the productivity of employees working from home during the pandemic increased by 5%. The report said that these results are consistent with a growing body of literature on work-from-home. (Barrero, Bloom and Davis)

Research by workforce consultancy Mercer found that 90% of employers say that productivity has stayed the same or improved with employees working remotely. (Mason, O'Rourke and Sardone)

Employers should rather worry about their employees working too much.

Mercer found that work-from-home employees are working three hours longer on average each day.

In the midst of the forced work-from-home revolution, the Harvard Business Review reports that “burnout — defined as ‘chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed’ — is at an all-time high.” Pandemic fatigue undermines productivity and contributes to anxiety and stress. (Thomason)

27% of all remote workers report difficulty in unplugging. (buffer.com) In a sense, if they work from home then they are at work nearly all the time. Paradoxically, employees worry that they’re not seen, literally to be working. Many have already felt the effect of Proximity Bias. Bosses have rated co-located workers higher than remote workers performing at the same standard. Intuitively aware of this, employees are anxious about their work performance not being visible.

Compounding the problems of routine work-from-home, 92% of American remote workers postponed, cancelled or didn’t plan any vacations last year. This is plainly unsustainable.

Despite these serious problems, 98% of all workers who’ve worked from home want “flexible working arrangements” (NB not just work from home) as a permanent component of their workplace arrangement. (buffer.com)

The conundrum for employers is that they must find a way to discover the truth about what employees really want, uncoloured by their own bias and recognising that the answer is dynamic.

Where this will land: Hybrid.

The United States is well past the era of work-from-home mandates. There has been a material increase is quit rates, but as stated above, this could be a temporary overshoot on the return to a trend that’s been on foot for ten years. Nevertheless, there has been a very significant shift in priorities for employees who’ve been working from home: by and large they do not want to return to the office 9 to 5, five days a week. (De Smet, Dowling and Mysore)

There has been some reluctance by employers to offer flexible working arrangements as a permanent feature of employment conditions. But there are precious few, if any reasons to hold on to this position. Many high-quality studies have proven that employers almost always benefit from work-from-home arrangements. The real issue is employee welfare.

Remote workers work longer hours and are more productive than when they are in office. But they suffer more burnout, and they take far fewer holidays. And of course, many report some degree of difficulty in connecting with their colleagues, despite their productivity increases.

If employers want to know how to respond to this new era, the answer is in practically every independent survey of workers: flexibility. Far more employees want flexible arrangements than want strictly work-from-home. Enter the era of Hybrid Working.

Some employers have heard the message.

To make the point, Telstra no longer includes location on most of its advertised jobs. CEO Andy Penn says “it’s about how you work, not where you work.” In a recent interview, Penn said that all employees in roles that were previously office-based would be offered flexible working arrangements, that they call Hybrid Working. Significantly, nobody would be held to a rigid schedule of in-office versus work-from-home. Google and Facebook have made similar policy decisions.

The implications of a full adoption of hybrid working are significant.

Firstly, the employer needs to head off burnout. “Checking in” with employees is necessary but probably insufficient. Policies will need to ensure that vacation and other breaks are taken. Many US companies already offer unlimited vacations although this is hollow when practically all employees are postponing, cancelling or not taking their vacations. Workplace safety, a very high priority for the office, also needs to be considered for the home office.

Having resolved those issues, the physical structure of the office will change. Many individual workstations become redundant. Some leaders are already predicting that the office will become the meetings hub. Employees will come into the office for meetings with colleagues and then return to their favoured workplace (the home, for most) to work individually and uninterrupted.

The corollary of this shift in the structure of the office is that real estate agents are already reporting significant increases in demand for home offices. It is now the third most important feature of a home, after the Kitchen and “outdoor entertaining area”. Two years ago, Home Office did not even make the top ten. (Casey)

We don’t know where this will end up because we’re in the midst of what Microsoft calls The Next Great Disruption. Only the most disconnected managers expect that we will snap back to pre-Covid conditions.

Conclusions

- Surveys of employee intentions to quit are very unreliable predictors of actual resignations. This has masked the issues.

- All surveys show a very large increase in employee preference for flexible working.

- Employers are practically oblivious to the changes in preferences of their workforce.

- Unsatisfied demand always results in change but rarely in the demand. Employees are not going to give up on the preference for flexible working arrangements.

- Tech-heavy companies are leading the Hybrid Working revolution, partially because they enable it.

- It’s too early to tell where this revolution will land but significant change is certain.

Works Cited

Barrero, Jose Maria, Nicholas Bloom and Stephen J Davis. "Why working from home will stick." April 2021.

NBER Working Papers. 3 November 2021.

<https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28731/w28731.pdf>.

buffer.com. 2021 State of Remote Work. 2021. 3 November 2021. <https://buffer.com/2021-state-of-remote-

work>. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Job openings and labor turnover survey. 3 November 2021. 3 November 2021. <https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/JTS000000000000000QUL>.

Casey, Brendan. Demand for home office space growing among Aussie buyers during COVID-19. 6 August

2020. 3 November 2021. <https://www.realestate.com.au/news/demand-for-home-office-space-growing-among-aussie- buyers-during-covid19/>.

Cooban, Anna. 95% of workers are thinking about quitting their jobs, according to a new survey – and

burnout is the number one reason. 7 July 2021. 3 November 2021. <https://www.businessinsider.com.au/labor-shortage- workers-quitting-quit-job-pandemic-covid-survey-monster-2021-7>.

De Smet, Aaron, et al. It’s time for leaders to get real about hybrid. 21 July 2021. 3 November 2021.

<https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/its-time- for-leaders-to-get-real-about-hybrid>.

Demands. Perf. Billy Connolly. 1991. Youtube. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FbweXPVKPxg>.

Dingel, Jonathan I and Brent Neiman. "How many jobs can be done at home?" April 2020. NBER Working

Paper Series. 3 November 2021. <https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w26948/w26948.pdf>.

Kelly, Jack. Millions of workers plan to switch jobs in pursuit of life balance. 23 June 2021. 3 November 2021.

<https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2021/06/23/millions-of-workers-plan-to-switch-jobs-in-pursuit-of-a- work-life-balance-growth-opportunities-remote-options-and-being-treated-with-respect/>.

—. Why the Great Resignation is greatly exaggerated. 8 June 2021. 3 November 2021.

<https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2021/06/08/why-the-great-resignation-is-greatly-exaggerated>.

—Klotz, Anthony. The Covid vaccine means a return to work. And a wave of resignations. 30 May 2021. 3

November 2021. <https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/covid-vaccine-means-return-work-wave-resignations-ncna1269018>.

Mason, Lauren, et al. "The new shape of work is flexibility for all." 2021. 3 November 2021.

<https://www.mercer.us/content/dam/mercer/attachments/private/us-2020-flexing-for-the-future.pdf>.

Microsoft. The Next Great Disruption Is Hybrid Work—Are We Ready? 22 March 2021. 3 November 2021.

<https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/worklab/work-trend-index/hybrid-work>.

PWC. "What workers want: Winning the war for talent." 2021. The Future of Work. 3 November 2021.

<https://www.pwc.com.au/important-problems/future-of-work/what-workers-want-report.pdf>.

Stephens-Davidowitz, Seth and Steven Pinker. Everybody lies : big data, new data, and what the Internet can

tell us about who we really are. New York: William Morrow, 2017.

Thomason, Bobbi. Help Your Team Beat WFH Burnout. 26 January 2021. 3 November 2021.

<https://hbr.org/2021/01/help- your-team-beat-wfh-burnout>.

1 The Sunday scaries are a type of anticipatory anxiety reflecting the nervousness you may feel the evening before the start of the workweek. – indeed.com

----------------------------------------------

Neville Jones is Chairman of DPR&Co, the owner and CEO of Experiential Travel and a former partner at Accenture.